General Introduction

Content and Significance of Jane Loraine's Recipe Book

James McCoull

The manuscript contains 78 folios including the contents page, and these are numbered in pencil on the recto of each leaf. The page numbers begin on f.3r, and go from 1 to 91, appearing only on the recto of each folio.

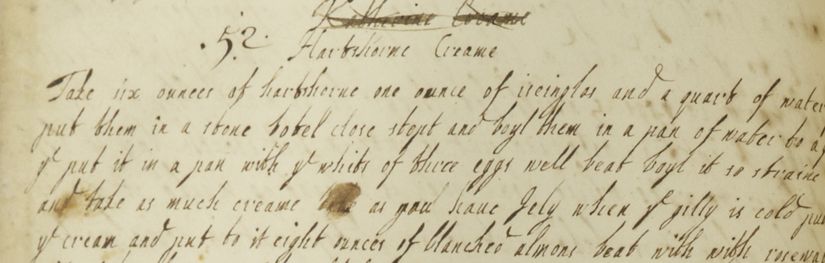

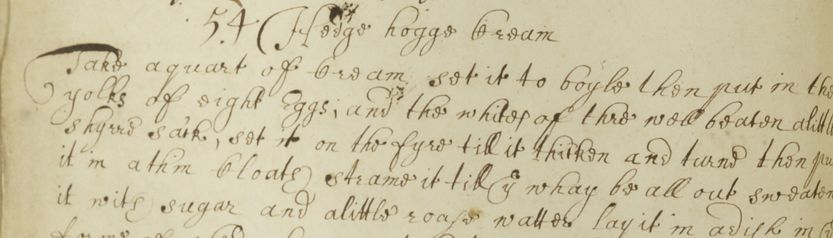

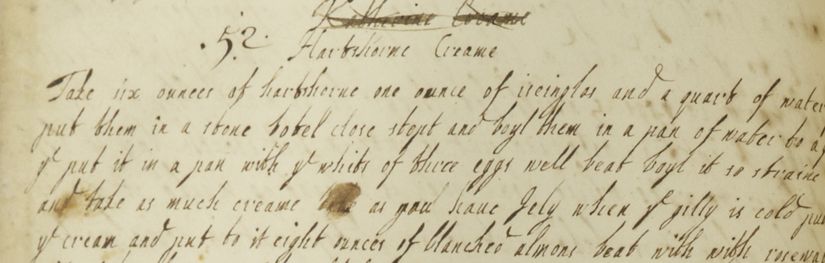

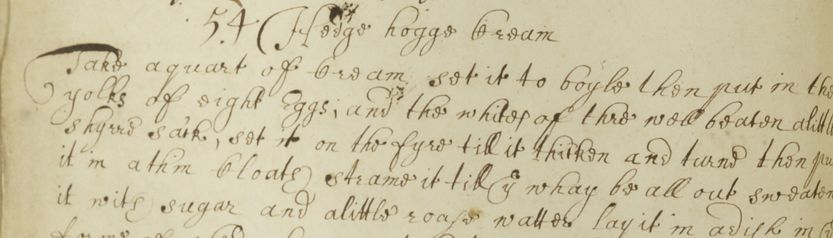

There are a total of approximately 622 recipes listed in the manuscript, which are inconsistently numbered. There are recipes numbered from 1 to 63, another group from 1 to 59, another from 1 to 44, another from 1 to 57, and another from 1 to 110, with a total of 289 unnumbered recipes mixed in throughout (the majority appear towards the end, with the last 238 recipes being unnumbered). The total number of recipes is approximate as the divisions between each recipe are inconsistent. Some are both unnumbered and untitled, and therefore the starts and ends of various recipes are difficult to discern.

This inconsistency of numbering is evidently due to the fact that the recipe book was assembled from collections of pages rather than being progressively written as a book, and as such the recipes have already been numbered for their own smaller collections prior to assembly. The folios are collected in a different binding from their original 17th century binding, and the pagination in pencil has been added retroactively to fit this new binding.

This text begins with a contents page containing 37 entries, each with the relevant page number attached. This page was evidently created for organisational purposes by the individual responsible for compiling the recipes together initially, as the page numbers have been added to each page after the recipes were written, fitting into whatever gaps are available. A note reading this appears throughout the manuscript, and this refers to the entries that have been selected to appear on the contents page.

Though the contents appears to list single recipes, the entries actually refer to where groups of variations on a recipe can be found: for example, remedies for rickets, scurvy and worms appear in their own sections, and the contents page directs to these sections.

There are various categories of recipe in the manuscript, including culinary, cosmetic and medicinal as well as combinations thereof, making Jane Loraine's recipe book an example of what Sara Pennell in Early Modern Women's Manuscript Writing calls a typical mixture of culinary, medicinal and miscellaneous veterinary and household advices: essentially, a kind of multi-purpose domestic compendium.

The sections appearing in the contents are sometimes for different recipes which are connected by theme, for example a recipe to prevent miscaring [miscarrying] which precedes one that is good for conception. An apt explanation for this comes from what Pennell calls the pedagogic habits of the middling sorts; this inclination to expand in multiple recipes and over numerous pages upon the author's relative areas of expertise seems to reflect their desire to share and demonstrate knowledge.

Though the contents are mostly in page order, there are three anomalous entries at the end of the contents: two for page 54 and one for 9. It is probable that whoever wrote the contents page added these entries after deciding they were significant enough to warrant an entry, having already written the rest of the contents. Though it is possible that the pages themselves were added later, they are unlikely to have been inserted at these points in the collected book rather than placed at the end to follow the page and recipe numbering conventions.

Different standards for division appear throughout, likely due to the different preferences and styles of the manuscript's various contributors. Whilst some sections have straight, solid lines dividing each recipe, others have dotted lines, and some have no lines or even spaces between recipes at all. This creates an inconsistent styling to the manuscript whereby some pages appear sparse and neat, and others are densely loaded with text. There is also a massive variation in the length of the recipes included in this book: some are as short as one line, whereas one recipe on f.48v is almost two pages long from start to finish.

According to Michael Hunter, in the Renaissance [secretary] hands were challenged by a revival of italic, and by the seventeenth century secretary gradually died out, being replaced by either italic or by round or mixed hands, characterised by more rounded and looped letter forms. This change can be seen in the manuscript as a mix of hands are present, including the looped hand to which Hunter refers, which appears on f.10v, as well as various other places. The italic hand is also prevalent, and appears to have been the hand of the main compiler as this is used for the contents page.

Though the manuscript pages are largely undecorated, using paratextual inscriptions such as swirls only to signify where some recipes end, there are some signs of aesthetic consideration evident in the ornate capitalisation used inconsistently throughout. Various recipes begin with large, elaborate capital letters, some even dipping down as far as three lines below the title.

Additionally, a recipe on f.31v has been deleted and restarted twice over (although no mistakes are visible) each time with a more elaborate first letter, the final attempt being written in a different hand. It is apparent that the presentation of this recipe was important to whoever wrote it (based on the name of the recipe, this is probably Mr Bates), so much so that they may have ultimately left someone else to write it out for them in a more favourable style, or otherwise chosen to deliberately change their own handwriting.

As Pennell suggests, manuscripts such as this were sometimes considered pages in which to hone one's handwriting. Evidently, graphology was a point of pride for the various contributors to this recipe book; the appearance of the manuscript as a result of this experimentation, however, was not, as the untidy, scribbled marks across the deleted recipes indicate.

The use of contractions occurs inconsistently throughout, with both ye and the appearing sometimes even within the same block of text, as is the case at the end of recipe 59 on f.10v. Hunter states that this is due to the ongoing change away from the archaic Anglo Saxon thorn (replaced by a y to mark the same sound), and claims that in the mid to late seventeenth century there is extreme variation as to how far they were used by different individuals.

What is interesting about this trend in the recipe book is that in many instances both forms appear to have been used interchangeably by the same authors. As Hunter said it was a period of shift from y to th, it is possible that individual writers were beginning to introduce this form into their writing slowly rather than all at once.

The change in handwriting is hard to determine precisely, as only Jane Loraine has a consistent tendency to sign her name on the pages. As such, our transcription ignores changes in hand, as this could signify a new writer, a change in ink or quill, or the passing of time, as well as any number of other factors. Handwriting styles vary frequently, but do not necessarily denote a new writer.

The various recipes included in the recipe book share several common ingredients, including milk and rosewater. These recurring ingredients tend to be ones which were readily available to people at this time, especially in an agricultural area where there would be abundant livestock, as milk and other dairy products are popular ingredients (more information on food in the period can be found in the Historical Context section of this introduction).

Additionally, these ingredients tend to appear in great quantities even within the recipes themselves: one recipe for Spanish cream requires three gallons of milk, which produces enough cream that it fills three earthen pans. Another requires 30 ayle pints of milk. These recipes evidently produce a large amount of food (in this case, specifically a large amount of cream), and as Pennell suggests the excess was likely intended to produce leftovers that found their way to the servant's table.

The wide varieties of cream present in this recipe book imply that Jane Loraine's household was wealthy. As Joan Thirsk notes, ordinary folk [could] rarely have indulged in separating [cream] from the milk, and so not only the large quantities of cream which appear in this recipe book but also the range of cream recipes themselves indicate wealth, and an abundance of spare time with which to experiment with this indulgence.

Various recipes use vague measurements and quantities for their ingredients, such as a recipe which calls for tow or four whites [of eggs]. This is likely due to a necessary uncertainty in cooking that Pennell identified: she said practice was the only means through which the recipe text could be tried and move beyond being a mere prescription.

The recipes in this manuscript are, in most cases, far from a finished, refined set of instructions: they record the attempts of the author, which others may edit or update with their own experimentation. This is elsewhere evident in recipe titles such as Goosberry wine ye best, appearing on f.74v, which reflects the tendency to alter and improve upon existing recipes until they reflect the highest quality that can be achieved.

The Mystery of Jane Loraine

Amy Moore-Holmes

Thirteen signatures in the Jane Loraine recipe book can be attributed to Jane Lorraine herself, indicating her to be the owner of the manuscript. The figure of Jane Loraine has largely remained a mystery due, in most part, to the subordinate position of women in the seventeenth century and the lack of historical material detailing their lives.

There are two primary candidates in identifying Jane Loraine, both are members of the Loraine family of Kirkharle, Northumberland. The Loraine family were an upper class family, elevated by King Charles II to a baronet of England in 1664. The Pedigree and memoirs of the family of Loraine of Kirkharle (1902), by Lambton Loraine, details this elevation, attributing it to the sending of thirty foot soldiers to Ireland to protect the plantation of Ulster by Thomas Loraine.

Thomas Loraine, born 1637, served as 1st Baronet during the composition of the recipe book. In 1657 he married his cousin, Grace Fenwick, at Hexham Abbey and in 1666 his eldest daughter was born, Jane Loraine.

Although there is a significant amount of historical material relating to Sir Thomas Loraine, 1st Baronet, very little is known about his daughter Jane. The 1st Baronet succeeded his own father, also Thomas Loraine, as head of the family at the age of twelve, following his father's premature death from a fever. At age twenty he married the fifteen-year-old Grace Fenwick; records indicate they had nineteen children in total, fourteen sons and five daughters. However, Lambton Loraine disputes this figure, noting that only seven children have been definitively traced.

Jane Lorraine is named in Thomas Loraine's will as his fourth issue after her brothers William, Thomas and Charles. Her birth date is given as 1666 suggesting that, if she is the author of the Jane Loraine recipe book, she was eighteen at the beginning of its composition in 1684. This corresponds to the round hand Jane Loraine employs within the text, as demonstrated on folio 33v. In Early Modern Women's Writing, Heather Wolfe notes that non-cursive semi-formal italic style of handwriting was the hand predominantly used by women in the first half of the seventeenth-century. However, by the end of the century most men and women had adopted the round hand. Thus, a round style of handwriting, as demonstrated by Jane Loraine, is generally associated with a person born mid-century or later.

Jane's mother, Grace, died at the age of sixty-two on the 2nd December 1706. Her father, Thomas, subsequently died on the 10th January 1717, aged eighty. His will details two further daughters, Mary and Katherine, although no subsequent information about them is known. William Lorraine succeeded his father to become 2nd Baronet in his sixty-first year.

Through her presence in her father's will, it can be deduced that Jane Loraine lived at least to the age of fifty-one, although whether she married or had any children is unknown. It is important to recognise that the dearth of historical material specifically relating to women of the period makes it difficult to attribute the text to any individual.

Lambton Loraine further details a Jane Lorraine, daughter of an Anthony Loraine of Walker or St. Anthony's. Anthony Loraine witnessed the marriage of Thomas Loraine and Grace Fenwick before his death in 1669. He named two daughters in his will: Jane and Grace. This Jane Loraine is additionally mentioned in the will of the 1st Baronet as his third cousin in 1717. Although no further information is given relating to this Jane Loraine, the reference to her in both wills indicates that she was living during the period of the text's composition and she must therefore be considered a candidate for the primary authorship.

At least thirty-one other individuals appear in the Jane Loraine recipe book. The most prominent name after Jane Loraine herself is Fenwick. On folio 36r the name Fenwick appears multiple times. This is unsurprising as it can be understood that these two prominent families of the Northumberland area were heavily intermarried. The 1st Baronet's wife, Grace Fenwick, lived during the text's creation.Grace's grandmother, furthermore, was a Grace Lorraine who had married Sir John Fenwick.

Many other prominent family names appear in the text such as Lady Gray of Chillingham and Horton and Mrs Dorithy Heron of Chipchase. The extensive contact between different families is highlighted by the depiction of the Loraine family coach visiting Sir John Swinburne at Capheaton Hall, preserved in the Swinburne's family record.

Interestingly, the names of several doctors are attached to medicinal recipes within the text, such as Doctor Mathias on folio 71r. Mathias is a Huguenot name brought to England by refugees in the seventeenth century; it gained influence in predominantly Western areas of the country such as Wales and Lancashire. This suggests informal networks of knowledge exchange between women and doctors in the period.

It is unclear to what extent the various different individuals mentioned actively contributed material to the text or whether their names have been attributed to recipes by Jane Loraine. However, the Jane Loraine recipe book can be understood as a social text, representing the communal nature of domestic knowledge in the early modern period. As a text, it offers a unique insight into the seventeenth-century household and the perspectives of the women that ran them.

Summary of the Critical Field

Sarah France

Sara Pennell and Michelle DiMeo have claimed that recipe books from the early modern period have only recently received mainstream attention from academic scholars, and most notably, have not traditionally been seen as important sources beyond particular disciplinary arenas.

Developing research has begun to reflect the diversity of purpose and meaning that modern scholarship stands to gain from recovering and using these manuscripts as a source of academic study, exploring their cultural significance beyond solely food history. Recipe books act as starting points from which to delve into the domestic world of the early modern period; they can be understood as culinary texts, medical texts, historical objects, or even a type of life writing. Studying them forges a picture of the social and cultural lives of the domestic sphere and of those who inhabited it. In this sense, scholars can examine how the domestic branches out beyond their initial assumptions and unearth a diverse understanding of the early modern household.

Gynocentric networks

Recipe books are highly significant in regards to gender studies, documenting a field dominated by women and providing researchers with a representation of wide gynocentric networks. These manuscripts depict the domestic sphere as a place where women held authority, not just in the home, but also in the community.

Critics have explored the implications of the social communities the recipe books were shared within; although the recipe books did have male contributors (see Historical Context), they were largely dominated by women. Elaine Leong notes that the majority of these recipe books were created by family collectives, who worked in collaboration across spatial, geographical and temporal boundaries.

The multiple hands and signatures within the books create a sort of historical palimpsest, telling the story of the manuscript as it is shared and passed down through generations. Daughters would inherit these books from their mothers, which lead to the books becoming what Sara Pennell describes as a particularly female construction, and moreover, a highly-valued focus of inter-generational routes for female-to-female communication.

Often we see a different hand editing a pre-existing recipe, or writing proved as evidence that they have practiced and successfully produced this recipe. This situates the early modern domestic space as a site of knowledge production and of positive interaction between women. Pennell writes of the importance of the mobility of these manuscripts, noting that textual mobility is the key to the creation and survival of these manuscripts [...] exchange of domestic information was a crucial medium of female association, conversation and friendship.

In observing the relations mapped out within these manuscripts, researchers can gain an insight into the female relationships forged in the period, and the use of recipes as a source of communication. Recipe books were a female domain, with the medical recipes often concerned with female ailments. Catherine Field explores a selection of recipes with an undercurrent of potentially controversial instructions: for example, inducing an abortion in the case of an unwanted pregnancy. The example given by Field is a recipe with a warning that excess usage may cause the death of a foetus: take them soone away, or they will cause her to cast all in her belly.

This is suggestive of a supportive female network prevalent within the period, as women would work to provide other women in different areas and different time periods with a means of control over their own bodies.

Empirical practices

Field also discusses the practice of proving a recipe, explaining how it allowed the individual to certify the receipts in her collection using her body as a testing ground for efficacy […] such testing was informed by an empiricist model of knowledge and an emerging scientific method which underscored the importance of personal observation and experiment.

This empirical form of practice reveals that women experimented in the kitchen in a similar manner to how early scientists were experimenting in laboratories, demonstrating a parallel development of empirical knowledge: they would practise the recipes and provide their own feedback and amendments, seen in the notes or edits within the manuscript. For example, the recipe To maike allmond milk within the manuscript is recommended to be used in order to treat the burning fever, and recipes for Plague Water are used to create a medicinal drink which would allegedly protect the drinker from the plague.

These kinds of medicinal recipes demonstrate that women were in fact essential to the development of early medicine, and so studying these manuscripts allows scholars to position them within the narrative of early modern medicinal development.

Authorial authority

Critical research also explores the ways in which recipe books such as these play with the complex notions of authorial authority. Critics must consider how to reconstruct the identities of the authors of these books, and how they can understand authorship in new ways.

Pennell and DiMeo note that the 'author' is an elusive quarry in many early modern texts, citing reasons as diverse as legal framework […] moral anxieties around the public persona of the author (particularly the female author) and the difficulties of assigning modern notions of authorship to certain text formats.

This is further complicated due to the nature of recipe books as a collaborative work, with multiple contributors who would often leave their entries unsigned. It is necessary to explore how to gain a greater understanding of the identity of the authors, and consequentially, of the early modern woman, when the authors within these texts are multiple and often not explicitly distinguished.

Is it possible to find an individual identity within a collective written identity? Field suggests that although The genre reflects a self that defies easy boundaries or definitions of singleness, [it] still projects an insistent emphasis on the identity of the individual through concern with practice and personal experience of recipes. Despite the complexity of multiple authors, the focus within the content on practicing and amending recipes allows critics to understand the individual within the collective.

The books challenge ideas of singularity not only in authorship, but in genre. Recipes would change fluidly between medical, culinary, and cosmetic, sometimes even belonging to two categories at once. This dispels normative concepts of these genres, encouraging a hybrid understanding of medicine and culinary recipes. Field writes that this flexibility fostered a correspondingly fluid self, constructed as positive, authoritative and capable of healing and being healed through the writing, practice, proving and exchange of medicinal and culinary receipts.

These recipe books reflect positive interpretations of the self and the body. Field explains how for the early modern period, writing about the self was generally understood as an attempt to govern the unruly, shameful body. For women in particular, writing the self was a complex process; women were faced with the task of writing about themselves whilst retaining the modest, submissive qualities expected from a woman of the period, which has in part resulted in the lack of female representation in manuscripts.

By turning to recipe books, women could draw on their domestic authority in order to justify their writing. Recipe books can therefore be understood as a textual space that enabled women's positive expressions of the self: their bodies were presented as healable, and capable of healing, instead of a site of shame.

Through analysis of these manuscripts, scholars can relocate and make visible the early modern female experience. Susan Leonardi makes an interesting association between the literal act of making and reproduction of recipes, and women's reproductive capacity. The female space of the recipe books allow a further representation of the reroductivity of these women, not solely through the act of bearing children, but through making, mending, and creating in all aspects of the household and community. Studying these recipe books therefore provides the opportunity to analyse and frame the female body as productive and reproductive in various ways.

Contemporary and practical research

The appeal in research on these recipe manuscripts goes beyond the methodological or archaeological approach; they provide access to other more practical disciplines, such as food technology.

There are a growing group of online sites which engage with the practicalities of making the recipes, having transcribed and modernised them for today's kitchens. Annie Gray states that it is only through studying [recipe books] in a variety of interdisciplinary ways that their full potential can begin to be realised.

Practical approaches to recipe book research allows analysis that reaches beyond purely the historical content of the recipe books, encouraging people to embrace a more tactile and material approach to the practicalities, and even taste, of the recipes contained within. Alyssa Connell and Marissa Nicosia, from the website project Cooking in the Archives, write that through engaging with the recipe book manuscripts in this way, the archives become much closer to our daily lives and the lives of our readers.

Newcastle University's library education officer Sara Bird organised an event in which pupils from Bedlingtonshire Community High School visited the university to create recipes from Jane Loraine's recipe books, working on the recipe for caraway cakes. Bird spoke of the importance of engaging with the public and allowing them access to the historical documents held in the archives: the students get to learn with academics who transport them back in time by creating a history trail […] The pupils really enjoy themselves and we get to share our expertise with them and show them that University is a fun and exciting place to be.

This type of hands-on research is a practical way to draw attention to the forgotten women of the early modern era, and could easily inspire people into doing further critical research on the recipes of these often overlooked texts and women. Events such as these provide universities with the opportunity to interact with the local community, feeding these recipe books back into the community networks from which they originated, in a manner that harnesses the collective and collaborative mentality that is reflected in works of this nature.

By transcribing this text, we are able to make it accessible to all, and as such, allow it to enter the current critical field of research. Digitising and making these recipes available to the public allows us as editors to add to the dialogue surrounding the early modern recipes, removing barriers of inaccessibility in order to improve research in a range of disciplines.

Pennell and DiMeo write that the 'intertextuality' of recipes makes them prime sites for conversing with the past, distant presents, and, in their mobility, even the future. Recipes provided the focus for vicarious and actual interaction with not only other people, but other times, places and cultures, and the compilation of a manuscript, or the reading of a cookery book, could take its makers far from the kitchen hearth – aesthetically […] geographically, socially and intellectually.

In sharing this manuscript, we are able to create a collaboration across temporal and spatial barriers, in a manner reflective of genre from its initial early modern development.

Historical Context of Women's Position in the Household and How People Cooked During the Period

Anja-Grace Schulp

During the seventeenth century the kitchen was a domestic space which provided opportunities for women beyond cooking and household tasks. The kitchen and, by association, recipe books, provided women with social networks and were sources of food trends, learning and scientific exploration. Recipe books can be seen as a clear source of female authority, with a historical value that goes beyond the recipes themselves.

The Jane Loraine manuscript serves as a prime example of this type of complex source, informing the reader of what food was available in early modern North East England, the historical context of women's position in the household and how people cooked during the period.

Aspirational and accessible recipes

Recipe books are useful sources for determining the types of food available in England at this point in history. However, critics must be cautious as some of the recipes featured in these books may have been aspirational, with some ingredients, such as imported spices, being relatively expensive.

Recipe books could therefore be utilised by the populace as a potential vehicle of social mobility, offering the possibility to the hopeful cook that s/he might learn from them how to concoct and present quality food. Despite the potential for aspirational recipes, more accessible recipes were also featured. There were also books devoted to cheap ways of feeding family and servants.

Essentially, recipe books covered a range of culinary styles from haute cuisine to modest domestic. The manuscript could be seen to apply to both aspirational and accessible recipes; recipes for desserts such as chocolate cream sitting alongside recipes for pap, a porridge like dish.

Food available in North East England

The Jane Loraine recipe book highlights regional food availability in the North East of England during the seventeenth century. Given the North East's shipping connections, records demonstrate that a lot of foreign imports were available at this time such as apples from France, oranges from Spain, almonds from Malaga and Barbary and West Indian spices via Antwerp and Amsterdam. There were also particular ingredients that were grown specifically in the North East such as Oats (that withstood both cold and rain) [...] to be used in pottages, porridges, and thick soups, which might account for the various recipes for foods such as pap in the recipe book.

Despite the potential for aspirational recipes, the quantities of the ingredients used in the manuscript can be used to infer a degree of availability. For example, the vast quantities of milk needed for some of these recipes reflects the amount of dairy available in the North East of England at this time. Many provided for their own needs at home by possessing a household cow, with a cow being the commonest possession of country people in terms of livestock.

The manuscript essentially informs the reader of the historical food trends in North East England, from the quantity of dairy reflecting the more unctuous textures added to the aromas of the period, to the use of rosewater, musk and ambergris demonstrating the short-lived fashion for perfumed food that occurred during this period.

Recipe books and literacy

The ideological role of the compleat housewife emerged as a national exemplar towards the end of the seventeenth century, which meant that the housewife was regarded as an expert in both the running the household and culinary endeavours.

The culinary skills required for this complete housewife role were often not hereditary skills, or skills that were passed down through the generations. This was partially due to the ever-diversifying tastes of the period, but also due to the universal desire for domestic expertise, upper-class women embracing cookery and domestic tasks, rather than limiting this expertise to domestic servants. It is because of this new desire for universal culinary skills that recipe books came into common practice, as there was a new need for documentation.

It is for this reason that literacy became exceptionally important. Beyond the desire for improved culinary skills, society became more print-oriented. The increased distribution of weeklies, broadsides, periodicals and magazines created economic and social changes that subsequently altered existing communication structures. Therefore, literacy became a point of access to these economic and social changes, not just a method of attaining the ideal of the complete housewife.

In the domestic context through recipe books, women could engage in literate activities without censure, providing them with opportunities to learn and engage with literacy, granting them an opportunity to become better educated. Literacy became a means to indicate power, a way to signal standing and class, regard and authority, recipe books granting women these opportunities and the opportunity to engage intellectually in the wider public sphere.

Social networks

Recipe books can be regarded as a form of communication that was not influenced by class. Women were expected to teach children and servants to read during this period, providing opportunities for all women within the household regardless of class distinctions.

In order to gain the skills required to become the complete housewife, recipes and techniques were often passed between class boundaries. This very action goes against the contemporary and historical image that domestic servants were culinarily inexperienced and ignorant, whilst the upper classes were not involved within their kitchen or household.

Although it is difficult to ascertain the class of the contributors to the manuscript, what can be determined is that these recipe books became multi-authored collaborative works with recipes often attributed to other people, such as Lady Herron or Mrs Charleton in the manuscript. The recipe book therefore became an object of shared knowledge, but also a method of communication, providing opportunities for reading, writing and socialising across class lines.

However, these recipe books did not necessarily produce exclusively gynocentric networks. Rather than rigid gendered intellectual spheres, men and women's spheres of activity are not as exclusive of one another as popular ideology suggests. In the manuscript itself there are several male contributors such as Dr Mirons, Dr Burges and Mr Sands, despite the majority of the book being written by women. Therefore, whilst it is clear that recipe books offered far greater opportunities for women that would have otherwise been denied, and that they dominated the domestic space, these recipe books were also a method of socialisation for both genders.

Recipe books provided opportunities for universal communication that was not limited by class or gender, creating a unique space of equality. Whilst this does not necessarily guarantee equality for an individual or group beyond these books, the recipe book can certainly be seen as a vehicle that may engender social change, demonstrating the social power, influence and significance that recipe books and literacy granted women.

How people cooked in the period

Beyond the value of literacy, recipe books offered a form of scientific exploration, placing women in an authoritative position that goes beyond that of the domestic cook. This is evident in how people cooked during this period, recipes taking on a scientific approach firmly rooted in the process of trial and error, such testing was informed by an emerging empiricist model of knowledge and an emerging scientific method […], which underscored the importance of personal observation and experiment to attain accurate information about natural phenomena.

Cooking was an intellectual field, a form of empirical knowledge. In the manuscript there are various instances of recipes that have been tried and tested. There are multiple versions of certain recipes, often grouped together, with many being called Another of the same demonstrating the experimental process.

Some have been annotated in the manuscript with this, potentially demonstrating the preferences of the cook, although this may have been solely for forming the contents page of the book. However, it is still likely that significant or well used recipes were the ones that made it into the contents page, demonstrating this experimentation. This trial process may have occurred for various reasons, such as personal taste and preference, but also simply a case of seeing what worked and what did not.

Medicinal and cosmetic recipes

Aside from culinary recipes, cosmetic and medicinal recipes were also featured in these recipe books, demonstrating the multifaceted use of the recipe book as a source. In the manuscript we are given recipes to take away hare it Shall never grow and Make teeth white, demonstrating the cosmetic concerns alongside the medicinal and culinary.

Beyond these superficial treatments, food and medicine were seen as a related activity during this period. Culinary and medicinal recipes often occur together, with there being no firm distinction between the preparation of food and medicinal remedies. All ingestible substances were thought to be endowed with humoral properties that could have a beneficial or a negative effect on the body.

This overlap between culinary and medicinal allowed women to construct themselves as expert on anything having to do with the body under their care, a far more intensive intellectual task than merely experimenting with recipes. For example, in the manuscript, recipe 37 To maike allmond milk, is also used to treat one that hath the burning feavour, demonstrating an additional side to the domestic space.

Mass cooking

Recipe books also placed women in a position of authority outside of the family and into the public sphere, as mass cooking was commonplace during this period. This is due to the fact that alongside managing the household and its servants (if they possessed any), the housewives were expected to feed the household as well.

This may account for some of the vast quantities needed for recipes in the Jane Loraine book, such as three gallons of milk in recipe 29 To make Spanish cream. The gargantuan size of these dishes possibly reflects the origin of a recipe in a household (or published cookery book) where meals were designed to produce leftovers that found their way to the servants' table.

For many, if not all elite married women, this role in many respects was extended to the wider community. They were often expected to entertain in large numbers, with the wives ministering the ordinary medical needs of the whole 'community' dependent on the estate.

These recipes were made to feed households and local communities, something which as a result extended the authority of women from the private to the public sphere. Their role became one far more essential and necessary than the purely domestic cook. Not only are they in charge of feeding the household, but of keeping the household and community healthy and thriving.

Textual Introduction

The Manuscript

Julia Walton

Physical description

The manuscript material is paper. The page size is 8 1⁄2 × 13 1⁄2 inches (216 × 343 mm) Foolscap folio. Recipes are written in more than one hand in single columns throughout using almost the entire width of the page. The margin on the left is ¾", 15mm. There is no margin on the outer edge of the leaf.

Many of the leaves have been damaged and have been trimmed and glued by the binder. The ink is black/brown and no other colours are evident. The page numbering, added later, shows missing pages. There are blank leaves in 5 places: 11rv, 21rv, 30-31rv, 40-41rv (modern numbering). The recipes throughout the manuscript fall into three categories: medicinal, culinary and cosmetic. The blank leaves are within the culinary section and the medicinal section.

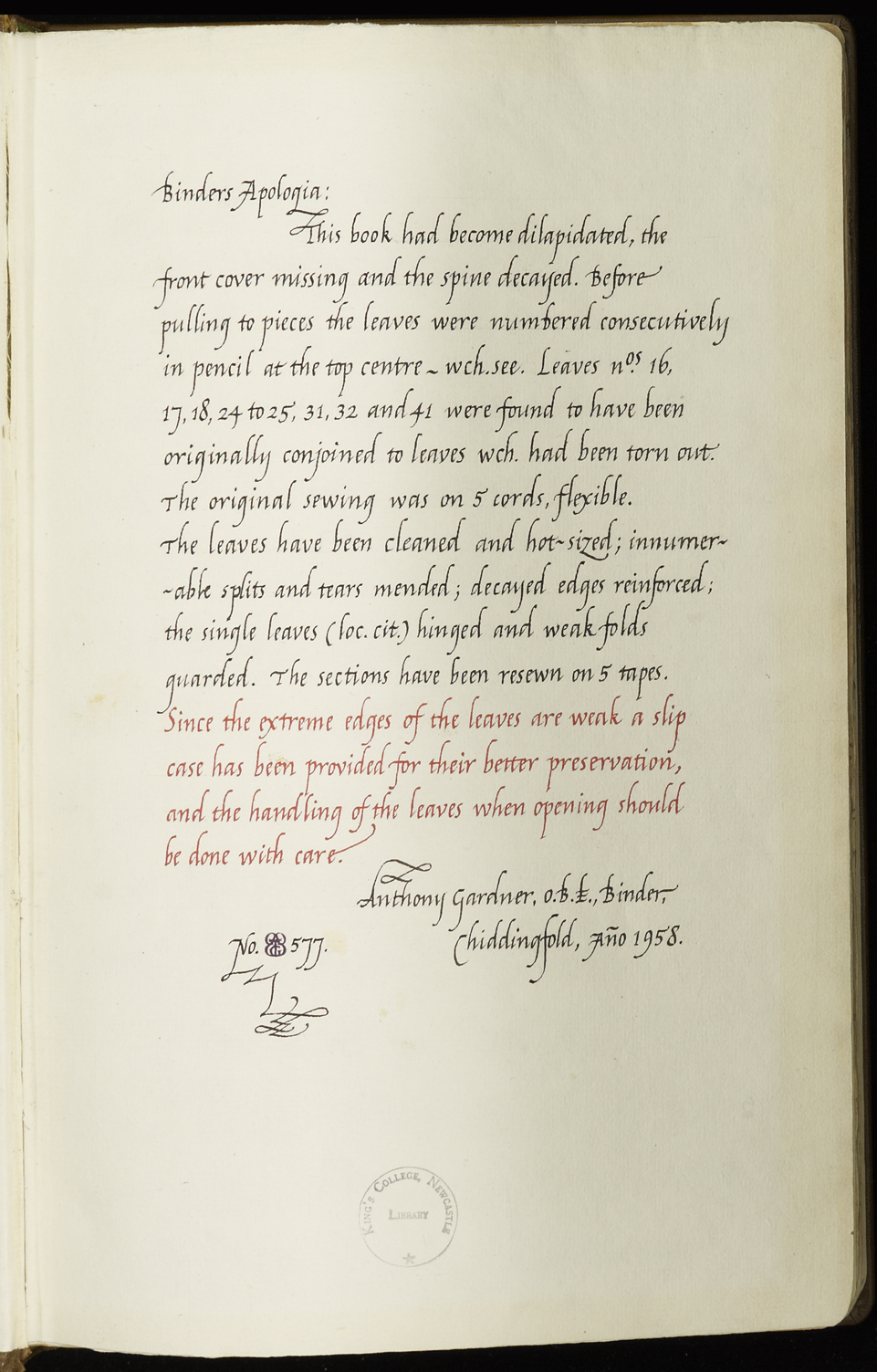

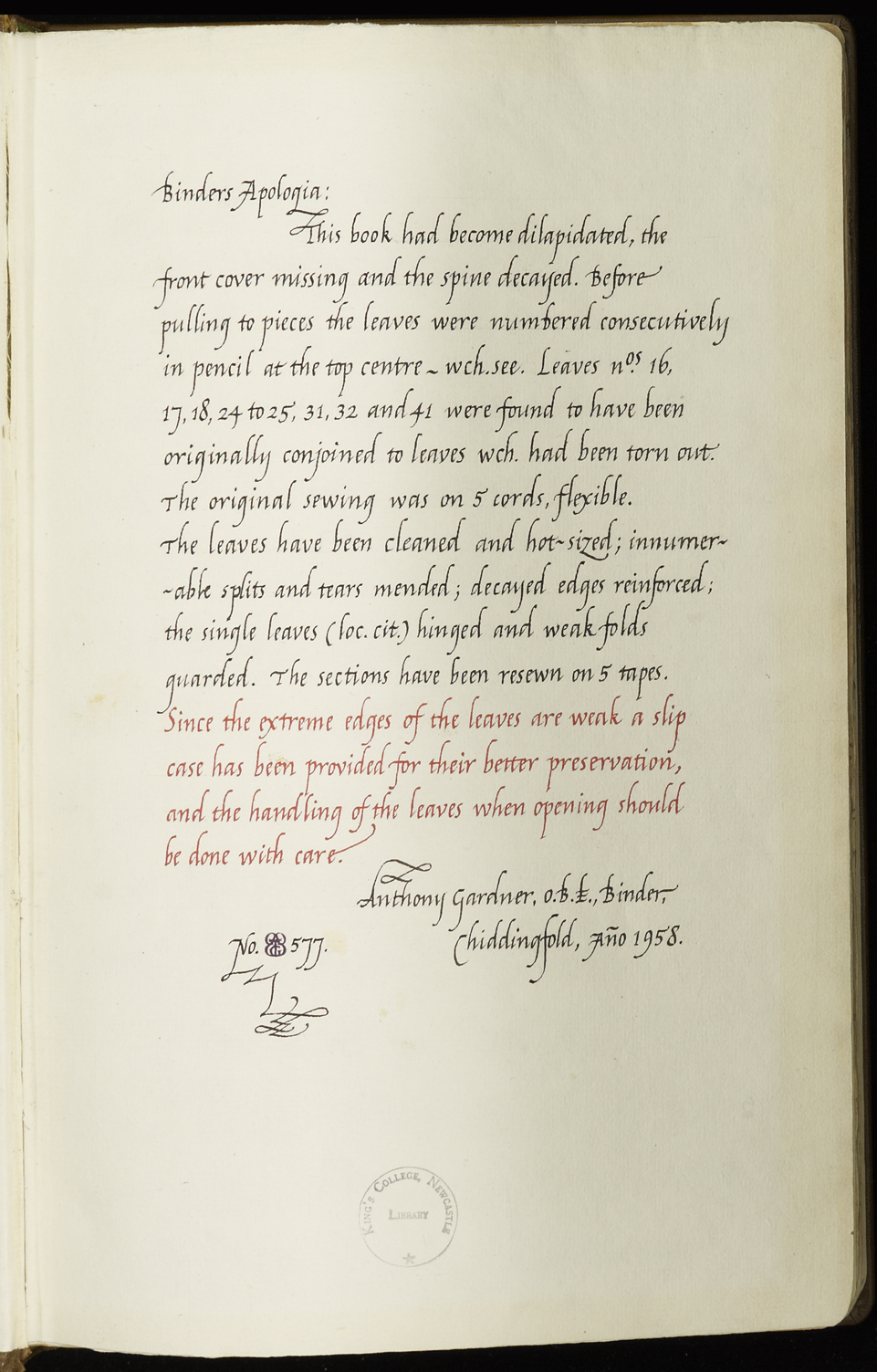

Binding

The binding is not original. The MS contains a binders apologia from Anthony Gardner OBE (1958) explaining that the front cover was missing and the spine decayed. The leaves were trimmed and sections resewn. The original sewing was on 5 cords, flexible.

from Anthony Gardner OBE (1958) explaining that the front cover was missing and the spine decayed. The leaves were trimmed and sections resewn. The original sewing was on 5 cords, flexible.

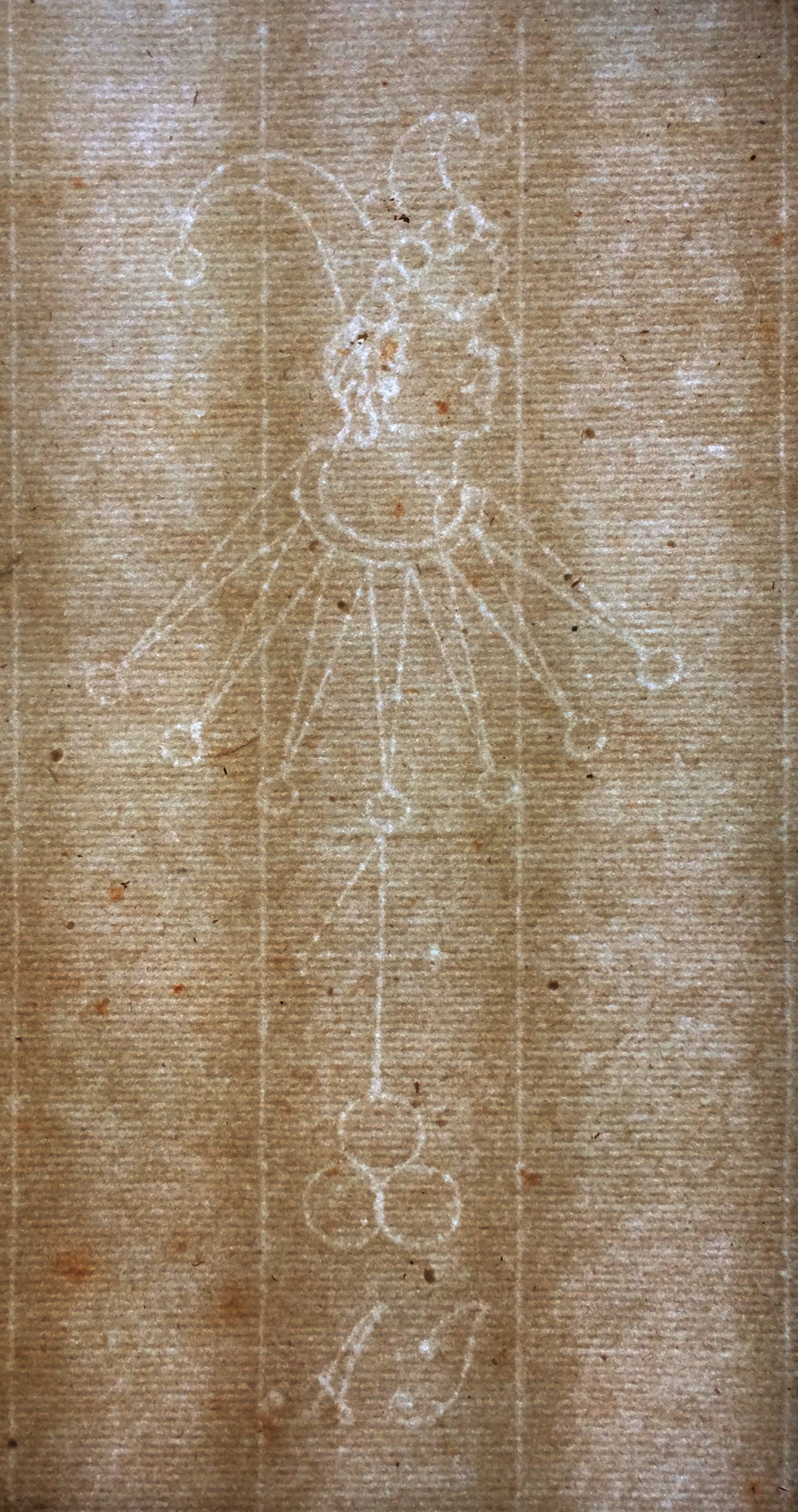

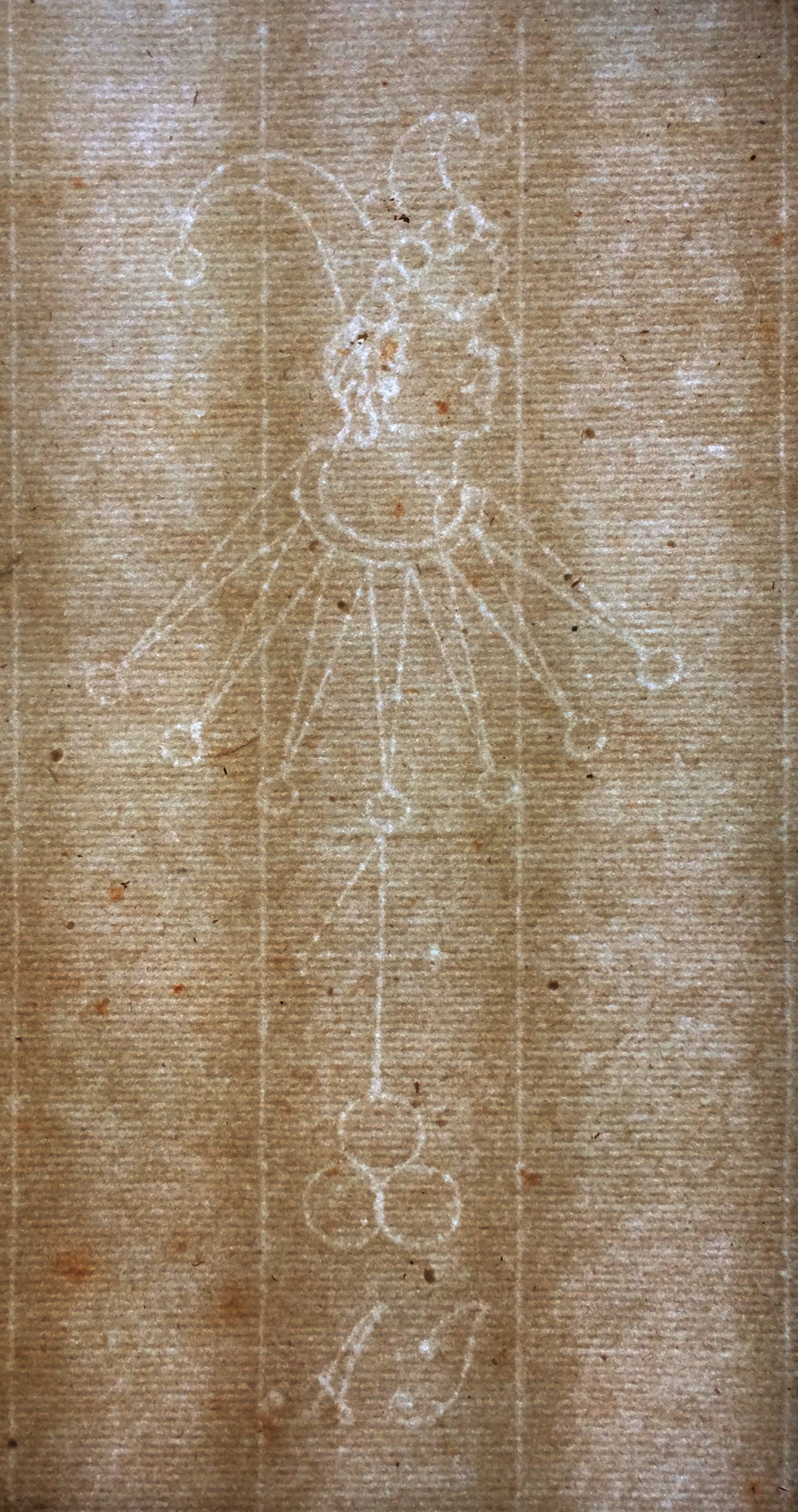

Watermark

A number of pages contain a single watermark categorised as a seven point Foolscap which appears in the centre of the leaf. The Initials AJ are in cursive below it. It appears on 39 of the 79 leaves of the manuscript, and occurs an almost equal number of times upright and upside down. The watermark is of medium size relative to the other watermarks in the Heawood catalogue. There are no other watermarks.

categorised as a seven point Foolscap which appears in the centre of the leaf. The Initials AJ are in cursive below it. It appears on 39 of the 79 leaves of the manuscript, and occurs an almost equal number of times upright and upside down. The watermark is of medium size relative to the other watermarks in the Heawood catalogue. There are no other watermarks.

Watermarks can be identified using catalogues compiled by Edward Heawood (Watermarks: mainly of the 17th and 18th centuries) and W. A. Churchill (Watermarks in Paper). Additional detail can be found in Edward Heawood's Historical Review of Watermarks (Amsterdam, Swets and Zeitlinger, 1950). Heawood states that The marks most used on paper exported [included] the Foolscap with seven points.

Heawood's catalogue contains an explanation of the initials AJ: towards the end of the 17th century makers or merchants often placed their initials in such characters [cursive] either below the mark proper, or on its countermark. The Dutch factor at Angoulême, Abraham Janssen, had his initials put below the shield bearing either the Fleur-de-Lis or some other hackneyed mark.

Paper

Heawood explains that the[re was a] considerable supply [of paper] to Great Britain from [...] France [...] in the late 17th and early 18th centuries. Although mills were at work in both England and Scotland in the late 17th century there is no definite proof that their products came into general use before about 1700. Heawood states that certain regions of France formed an important source of supply to the Dutch, and to a less extent also to the English market, many of the mills in Angoumios being run by Dutch capital. Angoulême is the former capital of the Angoumois province of France.

Research from Stirk and Isaac on the existence and output of English paper mills in the north east of England during this period supports Heawood's assertions. Isaac states that inconclusive evidence suggests that there might have been a paper mill in Newcastle upon Tyne from the 1760s or even earlier. Except for this Fourstones is the earliest mill in Northumberland, although there were several earlier in County Durham. Fourstones was established in 1763. At least two mills seem to have been in operation south of the Tyne around the end of the 17th C.. In Stirk's The Lost Mills, the first recorded example of a paper mill in County Durham is from the 1670s, with six listed for the county as a whole: Croxdale, Lintzford, Chopwell, Egglestone Abbey, Blackhall and Gibside.

There are two main reasons to doubt that the paper for the Jane Lorraine MS was produced by these mills. The dates of operation which are frequently after the dates in the MS, for example, 1695, 1697, 1717, 1719 and 1728, and the type of paper produced. In the case where the date corresponds with the MS, the type of paper may rule out the mill. Croxdale Mill, although operating in 1682, was not producing a suitable type of paper. The paper produced was mainly brown and whitey brown, relying on a cheap supply of rope from Sunderland port to use as the raw material. This is unlikely to have been of sufficient quality to be used for writing. Therefore, Jane Loriane's book is made up of paper sent into England via Janssen and such paper was used because of the poor quality and/or lack of paper production in England.

Hand

There are six different handwritings identifiable in the whole text. The italic hand and secretary hand

and secretary hand appear in this section of the manuscript and the secretary hand can be associated with Jane Loraine, through the 13 signatures given.

appear in this section of the manuscript and the secretary hand can be associated with Jane Loraine, through the 13 signatures given.

History

The manuscript was written in England in the 17th century, 1684-6.

Names

We have found 31 individuals throughout the manuscript by signature or because one or several recipes were attributed to them. Jane Loraine appears on several folios, including f.77. The other individuals are: Lady Attens (f.53), Lady Gray (f.36), Lady Heron (f.68), Lady Mary (f.46), Lady Morpeth (f.44), Lady Radcliffe (f.43), Lady Westmorland (f.65), Lady Winter (f.53), Dr Bourges (f.60), Dr Bowels (f.59), Dr Mathias (f.71), Dr Mirons (f.61), Dr Rumjye (f.64), Dr Sleuens (f.67), Mrs Boynton (f.46), Miss Charleton (f.25), Mrs Delavals (f.60), Mrs Dimotks (f.43), Mrs Doframby (f.66), Mrs Fenwick (several folios including f.36), Mrs Dorothy Heron (f.44), Mrs Heslops (f.54), Mrs Huits (f.46), Mrs Osborne (f.42), Mrs Ridal (f.69), Mr Sands (f.53), Mrs Sherriff (f.73), Mrs Sheules (f.53), Mrs Winsops (f.66), Mrs Withans (f.60).

There are 8 titled women and 6 doctors, which indicates that Jane Loraine's network included several titled families and members of the medical profession. This supports Leong's findings that recipe books of this period are often collaborative projects.

Provenance

There is no information available on the provenance of this manuscript.

Methodology

Lois Campbell-Dixon

The edition

The aim of this edition is to present the Jane Loraine receipt book, circa 1684-1686, as an accessible digital scholarly resource that preserves a piece of local North East England history.

This edition has been created using a sociological editing approach. As D.F McKenzie emphasises: the book is never simply a remarkable object. Like every other technology it is invariably the product of human agency in complex and highly volatile contexts which a responsible scholarship must seek to discover if we are to understand better the creation and communication of meaning as the defining characteristics of human societies.

Our edition explores this receipt manuscript as a socially created piece. The human agency discussed by McKenzie reaches beyond the idea of authorship to a focus on the text within a societal context, and this is how our edition has been approached. As it has no single concrete authorship, the contextual information provided on the text discusses how it is a work of social collaboration.

The themes of genre and gender both in relation to what this receipt book can tell of those themes and how they are relevant to the context of this text, have been explored within the contextual background.

Textual decisions

The source text is a manuscript existing in a single folio. It is a collaboratively produced fair copy of successive sets of culinary, medicinal and cosmetic receipts.

Transcription and mark-up

The transcriptions within this edition have been single keyed, and each of the editors has taken two leaves from the manuscript to transcribe.

Two versions of transcriptions have been created from the manuscript: one semi-diplomatic version and one modernised version. Each recipe has been given a descriptor of at least one of culinary, medicinal and cosmetic to allow for the reader to search the recipes using these key terms when a search function is later introduced.

Semi-diplomatic: The only editorial intervention within the semi-diplomatic version is the expansion of the abbreviations which is a common editorial practice for early modern manuscripts. This editorial decision was made to make the semi-diplomatic version to be of use to an academic or specialist audience; it may be relevant to researchers, teachers or students in the areas of food history, language history, literature and early modern history.

Modernised: Abbreviations and contractions are expanded. Words have been regularised to their modern equivalent within the modernised version. Archaic measurements have not been modernised, and instead have been defined within the glossary. The grammar of the original version has been maintained. This version is appropriate for an audience who do not specialise in the early modern period. By regularising words, we have made the modernised transcripts more easily comprehensible for readers without experience of manuscripts, or knowledge of the early modern period.

For a full description of the transcription rationale see the Guide to Transcription Conventions section.

Decoration and marginalia: The decoration within the source manuscript serves a purely functional role of separating recipes. We have maintained the separation of the recipes without the decoration as the digital images provide this for the reader. Where there is verbal marginalia it has been rendered; non-verbal marginalia can be found more clearly in the images than could be rendered through coding.

Interface

A left-hand side navigation menu has been used to allow readers ease of access to specific recipes, and which replicates a modern day recipe book in which users can go directly to a chosen recipe.

Four headers have been chosen to denote areas of the edition: Manuscript, Introduction, Commentary and Project. These terms have been chosen to clearly signpost the information available within this scholarly edition without overloading the interface with menus.

We have chosen complementary colours for font, background and menus to enable the edition to be read easily by a wide audience. We have chosen contrasting colours for text and background to make the content clearer for dyslexic readers.

The option to toggle between each transcript alongside the manuscript image has been included to enable readers to easily access the version of the text they require whilst exploiting the digital format by presenting the image always.

Annotations are presented in a hover box next to the term within the transcript. Readers have the choice to view or not view these annotations by clicking on the note icon. We made the decision to use hover boxes as it provides the annotated information alongside the text clearly, rather than using a footnote, and is a feature that is unique to a digital format.

Imaging

Digital images of the manuscript folios 1-30 are available in this edition. The images of the folios that have so far been transcribed, 1r-11r, have corresponding semi-diplomatic and modernised transcriptions. Images are a key part of digital editions and it is best practice to include them; as Patrick Sahle discusses, digital editions usually start with visual representations, are indeed expected to provide this evidence.

The use of digital images allows for the greater accessibility of the text via the digital medium and enables greater rigour through free comparison of transcriptions to manuscript images. As the source text is a manuscript, issues around handwriting must be negotiated: factors like the sharpness of the nib, the quality of the ink and the space available are taken into account, and this is an area where it is advisable to tread with caution.

We have made the editorial decision to not attempt to replicate handwriting styles or changes in hand within the transcriptions, as the accompanying images present the handwriting issues more appropriately than could be rendered within the transcripts.

Commentary

Annotations to the transcriptions are a key facet of a scholarly edition. We have chosen to include annotations to terms that are unusual or require clarity and appear infrequently within the manuscript. These terms are measurements that are not familiar to a modern audience, ingredient names that have changed over time or are unexpected items within a recipe, and some words or phrases that require clarity or context for comprehension.

We have also created a glossary of terms. Our rationale for words/phrases to enter the glossary is that they appear three or more times across the recipes that have, so far, been transcribed. This allows for the most commonly used unusual or unexpected terms to be defined and provided in an easily accessible list.

The commentary provided by the editors in the General Introduction gives contextual background to the manuscript from the period of its creation in the 17th century.

For a detailed discussion of the annotations we have included and the reasons why, go to the Rationale for Annotation section.

This edition so far

A digital edition cannot be given in print without significant loss of content and functionality.

This is the first phase of our edition and, with its current features, it could be given in print with minimal losses. As we have had limited time to create this edition, creating a resource that is accurately transcribed, accessible and scholarly has taken precedent over website features.

We have created a solid basis for a digital edition, and more features could be added to move the resource closer to Sahle's above definition. The inclusion of a crowdsourcing feature, hyperlinks to external websites and greater reader controls with layout and imaging are all elements that are unique to a digital format that could be incorporated in later stages of development.

The source text for this edition has featured in a Newcastle University community scheme, baking the recipes with pupils from local schools.

Guide to Transcription Conventions

Emily Burns

This edition includes two transcriptions: one semi-diplomatic version and one modernised version. Both transcriptions reproduce the original document in content. The reason for including two transcriptions is to give the viewer the option to choose between a version that offers every letter of the manuscript in clear font, as opposed to 17th century handwriting, and a version that was designed to benefit the modern reading experience.

As a rule, both transcriptions follow the original text as closely as possible in order to retain original meaning. In both versions, grammar and punctuation remain the same as the original. The spelling of family names has been retained in both versions to acknowledge the value the manuscript places on the few names that are referenced in the text.

Line breaks, page breaks and the placement of the marginalia are retained so that the transcriptions are similar in appearance to the manuscript. Words that do not have a modern equivalent in the original text have been retained in both transcriptions and an explanatory note has been included.

Illegible or missing words that appear in the manuscript are, in both transcriptions, enclosed in square brackets with underscores to indicate the illegible or missing letters: e.g. [sc--ding]. Words that appear in the margin of the original are indicated in both versions by underlining.

In the semi-diplomatic version, spelling and capitalisation follows the original text. Deletions made by the compilers are indicated with a strikethrough. Corrections and additions, which appear in the manuscript, are indicated with a caret: e.g. ^with^. Blank spaces that appear in the original text are indicated, in the semi-diplomatic version, by square brackets: [ ].

The two transcriptions also differ slightly from the original text for ease of reading. In the semi-diplomatic version abbreviations are expanded, and the introduced letters are italicised to indicate the expanded word. In the modernised version, expanded abbreviations are silently incorporated into the text. Words damaged due to the condition of the manuscript, but where the meaning of the words can be still inferred, are enclosed in square brackets in both transcriptions. Words that are repeated in the original text are deleted in the modernised version, but are repeated as in the manuscript in the semi-diplomatic transcription.

In the original text, the letters u and v are interchangeable, as are i and j. In the semi-diplomatic version the letters are retained, whereas in the modernised version the letters are replaced with their modern equivalents.

In both transcriptions, the size of the headers differ from the original, being one font size larger than the font size of the recipe text. This is to ensure that readers can differentiate between recipes and recipe headers.

In addition, the modernised transcription has made more changes to the manuscript to be able to offer modern readers an improved reading experience of the original text. In the transcription, the spelling has been fully modernised. Additions and deletions are silently incorporated into the text. Place names have been replaced with their modern equivalents. Capitalisation has been modernised, which includes removing capital letters that appear mid-sentence in the manuscript. Personal names and place names have been capitalised where they have not in the original. The first letter of a title and the first letter of a recipe have also been capitalised in the modernised transcription.

Rationale for Annotation

Emily Carroll

Why annotate?

Our project aim in creating a digital edition of Jane Loraine's Recipe Book was to allow access of the manuscript to a broad and varied audience. We therefore have created a rationale of annotation in line with this aim.

We recognised that in providing any annotation there is the potential to exclude readers, for example those seeking an authentic experience of the manuscript, authentic in so far as it is experienced as it would have been at the time of creation. However we have attempted to utilise the features of the digital environment, to make the edition as inclusive as possible.

Here we can hide notes to include an audience wishing to have an authentic experience, but also provide notes to encourage those, for example, looking for information on cooking, ingredients, and the history of the North East in the 17th century.

We have provided contextual information in our General Introduction, including information about the history of the book, its contributors, and more broadly about recipe books, gender and class in the 17th century. In providing this introduction we have a responsibility to annotate accordingly.

Our rationale for annotation is to provide clarity and understanding to encourage a wide audience of readers from a variety of backgrounds and to ensure accessibility of the text. As to which words specifically to annotate, our rationale is to annotate those words which may be unfamiliar to the modern reader and so require clarification or explanation to allow an understanding of the text.

We also recognise that in providing a modernised transcription of the manuscript, where we have updated spelling and expanded abbreviations, we open our edition to a wider audience. To this audience we must provide clarification on terms unfamiliar to the modern reader and examples of where this is used similarly in a modern context or provide examples of the word in use in receipt books or in domestic use from the time period of Jane Loraine's book.

Again we aimed to keep notation short and for the purpose of clarity, without implying too much interpretation. We recognise that this is possible only to an extent when providing examples. As Claire Lamont emphasises one of the aims of annotation is to remove obscurity and in annotating we are attempting to give the modern reader the knowledge which could have been assumed among the text's original readers.

Our initial intention was to provide neutral annotation, to provide definition for clarification. We felt that in order to allow as wide a reading as possible we had to avoid implying interpretation through annotation. However we recognised that, as Alice Eardley notes, in highlighting particular words for annotation we are already selecting words and suggesting that these require understanding.

By providing commentary as editors we are doing so from a particular societal perspective, as academics, in light of particular criticism and so annotation can never be free of interpretation completely. However, due to the nature of a receipt book, many terms being clarified are ingredients or cooking terms, and so there is no scope for interpretation, merely clarification.

Similarly we had considered the importance of allowing a free reading of the manuscript, one where a reader can experience the manuscript free from note or annotation. As Eardley suggests, annotation can [shut] down the text's potential for multiple readings.

We felt that to annotate could detract from the authorial intention and to provide opportunity to read the text online, as close to the original as possible, would allow a more authentic reading. This is where the digital edition allows us to work towards our aim to encourage a broad audience; notes do not appear within the text unless the reader clicks to open the note text box. Thus we avoid intrusive annotation, which allows the possibility of a free read.

How we will annotate

Annotations have been classified into three types: general notes, notes on ingredients, and glossary notes. Individual notes can be viewed at the relevant points in the text of the recipes, but all notes are also listed in the Editorial Notes section of the website.

Annotations are provided as short concise notes, with the intention of providing clarity and understanding to the modern reader. We should also provide textual information where relevant, for example on place names and people, in order to aid those seeking the edition in line with our intention, as set out in our General Introduction.

All notes will be given in the same format to provide continuity and clarity, with a definition where possible and then an example where necessary to aid understanding. Our aim was to use the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) for all definitions where possible, with examples largely from Early English Books Online (EEBO) and the Lexicons of Early Modern English (LEME). These are cited within the notes with the relevant abbreviations as above and the appropriate citation reference. Where examples are taken from open access sources, citations are again provided within the note, allowing our audience the opportunity to seek further information where desired.

We want to ensure the significance and value of the manuscript is not lost and can be appreciated from a variety of research disciplines. Although many may use the manuscript as a historical document, for example to gain knowledge about ingredients, history or domestic life, others may wish to recreate recipes. By the very nature of the manuscript being a receipt book written in the 17th century, many terms used are colloquial and archaic.

If one is wishing to recreate recipes, terms require updating so modern ingredients or equivalents can be found. For recipes to be successfully followed cooking terms and instructions must be clear and so an example of usage in the note will allow a reader to see how the recipe would be followed elsewhere. We feel that to provide annotation and commentary in such a way, enabled via the digital edition, will ensure the significance of the receipt book is not lost.

What will be annotated?

We provide notes for those words unclear to the modern reader. Therefore archaic language, dialect and cooking terms, measurements and ingredients common in the 17th century but obscure to the modern reader will be annotated. However, again, extensive description is avoided. Verbal marginalia has been included in the transcription, as per the Guide to Transcription Conventions, though notes are not provided on these. As high quality images of the manuscript are provided it is unnecessary to annotate such details.

Example note

All notes will adhere to the following style:

rosewater | rose water | roase water

Definition: Water distilled from roses or scented with essence of roses, used as a perfume or flavouring, or in medicinal preparations, etc. (OED: rose water, n.1.a).

Comment: The term appears both as a single word and two separate words in the manuscript. The citations in the OED show that current usage also varies between one and two word spellings, so the transcripts will maintain the spelling style of the manuscript.

Example: Take Claret Wine, Rosewater, sliced Orenges, Sinamon and ginger, and lay it vpon Sops, and lay your Capon vpon it, A book of cookyre Very necessary for all such as delight therin, A.W (1591) (Source: EEBO).

A note like this, with an example of the usage of the ingredient, will give the reader a better understanding, for example about the type of recipes it would have been used in, how it might have been used, or its popularity in the time period.